Pandemic Lessons Learned from the Spanish Flu

by Dr. Melinda Bossenmeyer, The Recess Doctor

Lessons Learned from the Spanish Flu

You may be wondering how, without medicine or a vaccine, the 1918 Spanish flu was extinguished?

By Dr. Melinda Bossenmeyer

My history lessons sometimes come from my family's diaries and letters passed down through the generations. This rare body of firsthand accounts, which we call primary resources in schools, didn't come from the Library of Congress (as is often the case in schools) but rather from my Great Uncle Charley Grubb, my Great Aunt Lizzie Doughty, my Great Aunts Cora and Lydia Morgan and my grandparents, Kenneth and Marie Knorpp.

It is always fun and educational to go to the family diaries and letters to see how they and other family members spoke of living through historical occurrences and their perspectives at the time.

Historical Perspective

A First-hand Account of the 1918 Spanish Flu

A First-hand Account of the 1918 Spanish Flu

Such was the case in a letter dated, October 18, 1918, during WWI. It was written by my great Uncle Charley Grubb who was part of a military police unit at Camp Travis in Texas. His firsthand account of the 1918 Spanish Flu mirrors the historical accounts of the experience of ordinary citizens living through the pandemic, written in newspapers. He wrote to his mother at home in Missouri. "I can tell you I'm fine and that is more than most of the boys can say. I was the Guard closest to the hospital the other night and Mother I sure saw some sights. They were taking the bodies to the train to ship home all night. I can't tell you how many die a day, but there is enough, and it is awful to see them handle the bodies. But we are in the army now."

What Uncle Charley wasn't aware of at the time was that the first wave of the Spanish flu began in March of 1918. And those that became infected usually recovered after several days. However, a second, highly contagious second wave of influenza that he was describing in his October 18, 1918 letter revealed that throughout the United States some victims died within hours or days of developing symptoms when their lungs filled with fluid that caused them to suffocate.

Healthy young people—a group normally resistant to this type of infectious illness—including the servicemen Uncle Charley observed in World War I were hit especially hard. In fact, more U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the war. Forty percent of the U.S. Navy was hit with the flu, while 36 percent of the Army became ill, and troops moving around the world in crowded ships and trains helped to spread the killer virus.

In the end, about 3% of the world's population died of the Spanish flu between 1918 and 1919.

Then and Now

Similar to today, in 1918 hospitals in some areas were so overloaded with flu patients that schools, private homes, and other buildings had to be converted into makeshift hospitals, some of which were staffed by medical students.

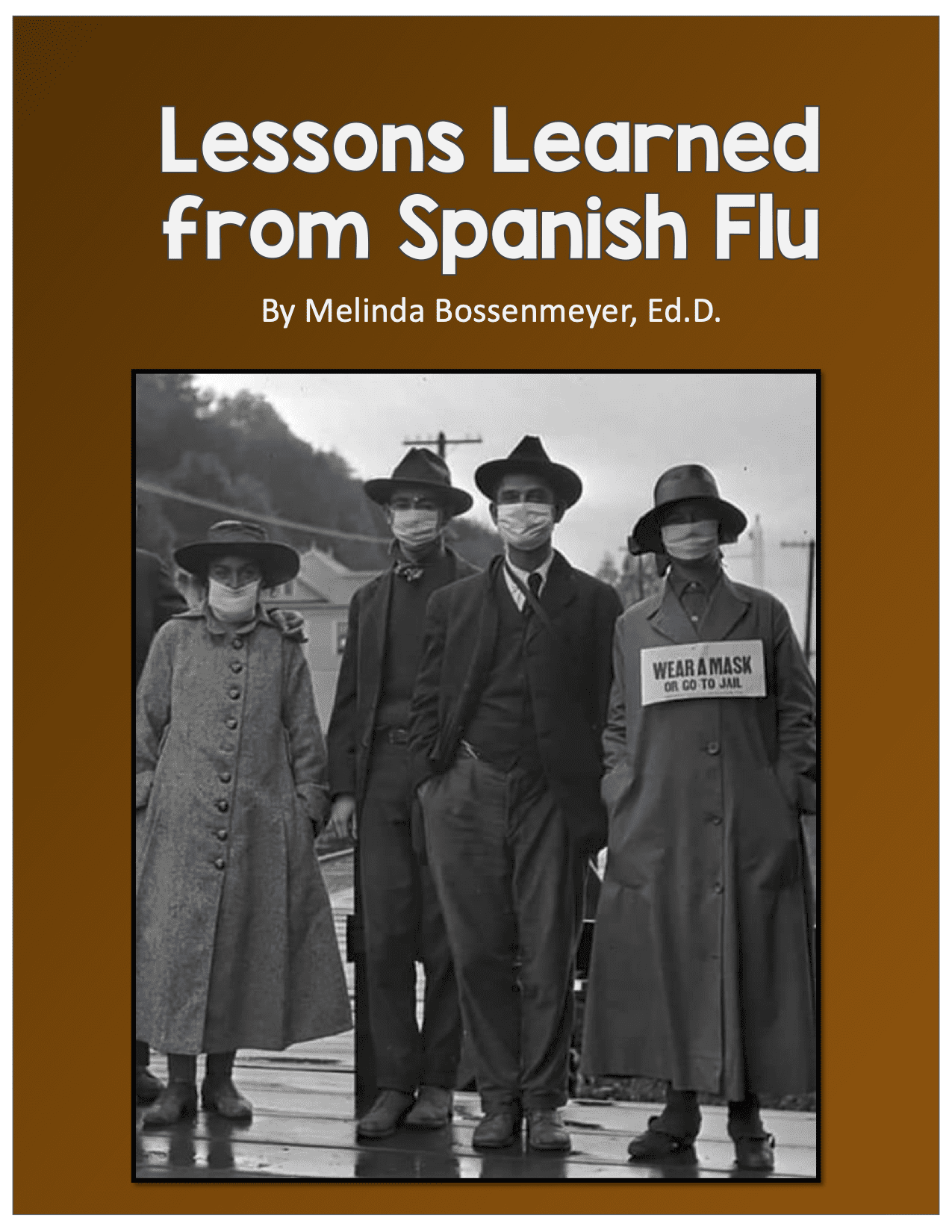

Officials in some communities imposed quarantines, ordered citizens to wear masks, and shut down public places, including schools, churches, and theaters. People were advised to avoid shaking hands and to stay indoors, and libraries put a halt on lending books.

Also like today, the flu was detrimental to the economy. In the United States, businesses were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Basic services such as mail delivery and garbage collection were hindered due to flu-stricken workers.

In some places, there weren't enough farm workers to harvest crops.

In the summer and fall of 1918, the situation got worse as returning soldiers infected with the disease spread it to the general population—especially in densely-crowded cities. Then, as we are experiencing now, they were battling an infectious disease without a vaccine or approved treatment plan.

How History Repeats Itself

Lasting just over a year, the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic is a reminder of how history repeats itself when governments and their citizens fail to meet a crisis head-on.

With the lack of national leadership in 1918, it fell to local mayors and health officials to come up with a plan to ensure the safety of their citizens. Due to wartime pressures to appear patriotic and with a censored media downplaying the disease's spread, many of those public officials made tragic decisions.

One particular example of a local decision that proved tragic was when Philadelphia's Dr. Wilmer Krusen, director of Public Health and Charities for the city, insisted mounting fatalities were not the "Spanish flu," but rather just the normal flu. On September 28, 1918, Philadelphia went forward with a Liberty Loan parade attended by tens of thousands of Philadelphians. That single miscalculation resulted in the spreading the disease like wildfire. In just 10 days, over 1,000 Philadelphians were dead, with another 200,000 sick. Only then did the city close saloons and theaters. In the end, by March 1919, over 15,000 citizens of Philadelphia had lost their lives.

On the other hand, St. Louis, Missouri, made a different decision: Schools and movie theaters closed and public gatherings were banned. Consequently, the peak mortality rate in St. Louis was just one-eighth of Philadelphia's death rate during the peak of the pandemic.

These same events handled differently, serve to illustrate how inaction, misinformation, and poor leadership can exacerbate the problem with far-reaching and even fatal results.

You may be wondering how, without medicine or a vaccine, the Spanish flu was extinguished?

Much like today, the Spanish flu did not just go away. It required mitigation procedures much like today. To limit the spread of the 1918 deadly disease, in the end, businesses closed, citizens were ordered to stay home, masks were mandated and heavy fines were implemented when people were in public without a mask. Large group gatherings were prohibited. Work hours were staggered so that fewer people were on the subways at one time for those essential workers providing care. Sound familiar? It should.

If history has taught us anything about how to deal with this pandemic, it is that we must "deal with it". We must voluntarily limit our freedoms and take personal actions that will protect ourselves and others from this deadly disease. Or, the alternative is, we will "Live with it" in a prolonged state of denial as the pandemic will be a long drawn out illness that will keep our economy at an all-time low, devastate families and finances, and it will cripple the future of a large number of Americans.

After mitigating strategies began to work, but not before a large number of citizens infected with the Spanish flu died, others who survived the flu resulted in herd immunity. Sometime in the Summer of 1919 the flu pandemic came to an end.

Good Times Ahead

Back to my letter from my Uncle Charley Grubb, his subsequent letter pointed out what is often the case after unilateral darkness – the light will once again shine through. Charley wrote, "I hope I don't get sick for I don't think we will be in the Army long. We get newspapers every 2 or 3 hours now telling about the peace terms." Charley was correct. On November 11, 1918, his letter began, "Well the war is over. We are having some time. Thousands of people are here today carrying flags and the bands played all morning. Whistles blew and there was lots of shouting. Mother this is the best news I ever heard and I know it is good for you."

WWI came to an end with the signing by President Wilson of the Versailles Peace Treaty. (As a historical note, Wilson's signing of the Treaty was delayed as he recovered from, you guessed it, the Spanish Flu. )