Inclusive Playgrounds: Fun for Everyone

by Dr. Melinda Bossenmeyer, & Karen Robertson

Inclusive Playgrounds: Where everyone belongs.

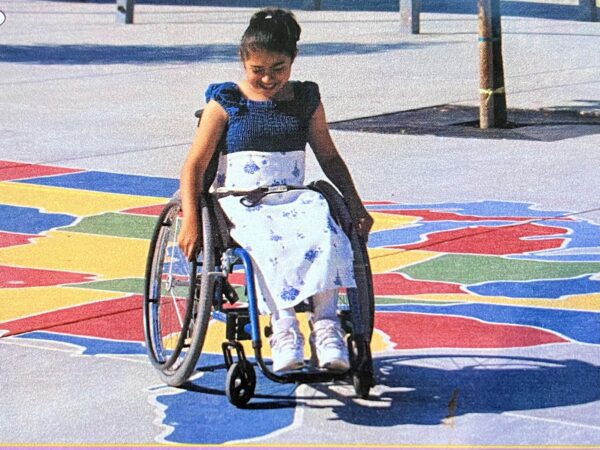

In sunny Southern California, where most days allow for outdoor play, there’s a playground program designed to ensure safety, encourage good behavior, and be accessible to every student. Just because a student has a disability doesn’t keep him/her off the playground where games are designed for educational value, as well as motor-skill development. For students with disabilities, the fun extends to everyone because everything is accessible because all games are at ground level.

It would be wonderful to look out over a playground and see children in every area laughing and playing peacefully, while supervisors observe without raising their voices, whistles, or blood pressures. A closer look at these playgrounds reveals concentric circles, rectangles, and various colored shapes, carefully spaced and painted on the blacktop. In addition to traditional games such as hopscotch and four square, imagine an alphabet grid, a number grid, and a skipping track. Children can even be seen “traveling” over a map of the United States, onto the ground.

Melinda Bossenmeyer, playground designer and safety consultant, created the Peaceful Playgrounds program in the 1980s. It originated when, as a physical education specialist, she was asked by her principal to develop a solution to disciplinary problems on the playground after every recess. Since then, she has become an internationally known speaker in the area of playground safety and accessibility.

The core of the peaceful playgrounds concept, is creating structured, fun, and inclusive activity on school playgrounds.

Five Main Guidelines

1) Grassy and Blacktop Areas are Painted with Colorful Game Markings

According to a blueprint, games are distributed evenly over the entire playground with plenty of room for students to maneuver wheelchairs. Where most programs focus on play structure areas and equipment, focus of this playground design is on blacktop and grassy areas. Colorfully painted markings on flat surfaces add 100 games and activities to a playground, without adding any structures, providing an appealing, almost amusement park look to the surroundings.

With so many choices, children have fewer conflicts and are dispersed in small groups throughout the play area. They are encouraged to choose a game where fewer than two are waiting their turns. Children wait in line less and play more so there is less impatience and more group camaraderie. When children know they will get their turns quickly, there is less reason to argue over rules. Being put out means a brief rest before being in again.

Instead of a raised balance beam, a balance beam is actually a painted line on the blacktop surface. Targets are painted on the ground for hand-eye coordination activities. Number and alphabet grids are painted also, allowing those who have paraplegia to participate successfully by tossing beanbags.

Markings also include skipping, hopping, and galloping tracks with footwork painted on the ground to add visual clues for students having difficulty learning locomotor skills. Since there is no lift or elevation in these areas, access is easy, and all surfaces comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines (U.S. Department of Justice, 1990).

2) All Students are Taught a Consistent Set of Rules

For the first three months of school, rules are posted on large charts outside and taught as part of the physical education program. Playground supervisors teach the rules during recesses and motor-skills classes. Rules never change. They guarantee equal opportunities to every student.

Another focus is on fairness and cooperation. Students with disabilities find ways, with help from their friends, to participate. They can turn a jump rope, play four square, follow the tracks, and participate in many of the other activities.

Some games are competitive, while others are cooperative. Freeze Out, for example, is a game where players work together to stay in.

A rule, or watchword, guarantees an inclusive environment. “You can’t say, ‘You can’t play.'” With the philosophy of “Invite others to join in,” a cooperative environment is created. Students are seldom drawn away for disciplinary actions.

Playground supervisors or other students help modify games for those students with disabilities. They assist them by doing such things as retrieving thrown bean bags or placing them in waiting hands.

3) Students are Taught a Procedure for Handling Conflicts

Walk, Talk, or Rock. Appropriate social interactions are taught so students have techniques for handling their playground problems and disagreements. Some of these techniques are

Walk

If a conflict arises, the student’s first option is to walk away and choose another game. Avoiding arguments is a valuable social skill.

Talk

Another option is to talk through the conflict using resolution strategies. If an argument persists or escalates, students must leave the game (and the play area) and move to another level of conflict resolution. There, they have to discuss the conflict, decide what part they each played in starting it, and apologize.

Rock, Scissors, Paper

This technique is a quick hand game used to settle simple disputes, such as a question over whether or not the ball landed in a line. Both children make a fist and use a pounding motion on their available hand simultaneously. On the third pounding motion, each child selects either rock, scissors, or paper to designate. In the case of a tie, they repeat the procedure.

A rock will break scissors, so rock wins over scissors. Paper will cover a rock, so paper wins over rock. Scissors will cut paper, so scissors win over paper.

The Rock, Paper, Scissors game usually solves most all playground conflicts. When the program is instituted, it is usual for school administrators to marvel at how simple this is and wonder why they did not think of it on their own.

Since most children do not want to leave the games, they soon learn to settle their differences swiftly. They also learn that whining to playground supervisors is not a solution because supervisors do not intervene on behalf of either child but send them away from the game to discuss problems. Teachers have found this conflict resolution model carries over into the classroom. Students work out their differences without the loss of relationships.

E Hale Curran School has been honored as a California Distinguished School and a Golden Bell Award winner. The merits of its playground program have played an important part in the overall excellence.

Results of a Six-Year Study

In 1992 at E. Hale Curran Elementary School (K-5) in Murrieta, California, educators began their own study. The school, housing 600 students, was 3 years old with a rapidly growing population. As the number of students grew, so did the injuries. In 1992 only 9 (28%) of a total of 32 accidents resulted in visits to a physician. By 1994, total injuries had risen to 51, with 22 (43%) serious enough to warrant a physician’s attention.

In 1995 the Peaceful Playgrounds program was instituted at this school. Every playground supervisor was trained in the new games and conflict resolution strategies. Every child was taught game rules and three methods of conflict resolution. A continuous motor skills program, taught concurrently by classroom teachers, enhanced the children’s abilities to participate successfully in game activities.

The district maintenance crew painted game markings on the blacktop and fields according to the blueprints and templates. The blueprints show measurements, layout, spacing, and game placement. They also provide an overall picture of the final design outcome.

By the end of the 1995 school year the population had risen to over 1,200 students, but total injuries had dropped by 50%. In 1996-97, the school population dropped, as many of the students moved to a new facility. By 1997-98, the school population had risen to almost equal the ’94-’95 school year, and yet there were only 9 injuries total. 17% of the 1994-1995 total of 51 (National School Safety Center, 1998).

In addition to injury reduction, another benefit realized was motor skill development. While it is not the physical education or adapted physical education program, most playground activities complimented the physical education program and lead to better motor skill development. This playground program provided more effective ways to increase learning in both traditional and non-traditional activities while providing a safer play environment.

4) All School Personnel Buy-In to the Program and Reinforce Rules Consistently

Teachers, as well as playground supervisors, are all trained in the rules of each game and need to fully support the program for it to be effective. Aides have aprons with award tickets, stickers, Post-Its, and materials used to reward students for good behavior.

Rules are strict, but when the whole school uses them over a period of years, they create a safe environment, and injuries become a rarity. None of the games allows for free-for-alls, and most include some educational element.

Each year over 200,000 children are injured on school playgrounds across the nation (Tinsworth & McDonald, 2001). That is, over 200,000 of them sustain injuries serious enough to send them to the physician or hospital. The district nurse attests to the astounding decrease in playground injuries after the playground program was implemented. “The statistics tell the story” (Bossenmeyer & Owens, 1999).

5) Necessary Equipment Must Be Available

Just as books, paper, and pencils are necessary equipment for successful academic instruction in the classroom, the proper equipment is just as important on the playground. All the markings in the world will not help without ample equipment.

A central storage room, with students in charge of check-out and check-in of equipment, is the most desirable system. An assigned supervisor can monitor the check-out and retrieval, as well as inventory and maintain equipment. Distributing equipment from each classroom is not effective, resulting in too much loss.

An air pump should be in the equipment room so playground balls can be properly inflated and quickly put back into play. A general rule of thumb is there should be a minimum of one piece of equipment for every 10 students on the playground at any given time, or at least one for every game (Bossenmeyer, 1999). The life expectancy of a playground ball, if used correctly, is one year and, therefore, should be budgeted for and replaced accordingly (Bossenmeyer, 1989).

Concluding Comments

Playgrounds of this nature have spread across the nation. Family Circle Magazine mentioned the program in its “Play Nice” piece in the April 1, 1998 issue. School Safety Magazine published an article on the merits of the program, and Dr. Rhonda Clements, author of Elementary School Recess, included an entire chapter in her book. Full inclusion can be accomplished on the playground, as well as in the classroom…and what better way than in organized games and activities?

Selected References

Bossenmeyer, M. (1999). Peaceful playgrounds: Activity guide K-3. Canyon Lake, CA: Bossenmeyer.

Bossenmeyer, M. (1989). Peaceful playgrounds: An elementary teacher’s guide to recess games and markings. Canyon Lake, CA: Bossenmeyer.

Bossenmeyer, M., & Owens, C. (1999). Safe & peaceful playgrounds program. Unpublished. Long Beach, CA: Bossenmeyer.

National School Safety Center. (October, 1998). Peaceful playgrounds: Minimizes injuries and confrontations. Malibu, CA: Pepperdine University.

U.S. Department of Justice. (1990). Americans with Disabilities Act. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Tinsworth, D., & McDonald, J. (2001). Injuries and deaths associated with children’s playground equipment. Washington, DC: U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.1

Melinda Bossenmeyer is an author and international speaker. She is the creator and President of Peaceful Playgrounds and is currently the Director of Professional Development at California State University, San Marcos. Karen Robertson is an author, speaker, and Personal Success Coach.

Melinda Bossenmeyer, Ed.D. is an expert witness for school supervision, playground injury cases, physical education, and coaching cases related to supervision. Professional articles by Dr. Bossenmeyer © Peaceful Playgrounds 1998 All Rights Reserved

Insights & Resource

OPST Sample Course Form

"*" indicates required fields

Informative article Melinda! An estimated 500,000+ children are injured in playgrounds every year. While playground supervision should be well designed, leaving no blind spots, it’s also important to teach children the importance of waiting your turn and not pushing and shoving to get others out of their way.

I liked that you said that there must be a supervisor in a playground for every 32 children to ensure their safety. Actually, my husband and I bought a new property that has really spacious lawn, and we are thinking of installing an outdoor playground next month for our two children. We will be sure to always be on the lookout whenever they are playing around. Also, we will start looking for a playground equipment supplier.

This is a recommendation from the National Program for Playground Safety.

Ensuring adequate supervision and proper training for playground supervisors is essential for child safety. It’s crucial to establish clear communication channels and emergency procedures, especially during outdoor activities. Implementing supervision zones can enhance oversight and minimize risks, providing a safer environment for children to play and learn.